|

| Dutchwoman Butte viewed from Forest Road (FR) 60 about a mile east of its intersection with FR 895. The butte’s 100-acre summit lies roughly 1,000 feet above the surrounding terrain. |

| FR 895 proceeds north from FR 60 and passes within a mile of the easiest hiking route to the butte’s summit. FR 895, although safely traversable by an off-road vehicle, might have caused severe damage to my low-clearance vehicle. Consequently, I established a camp at the intersection of the two roads and from there walked the additional three miles on FR 895 before venturing cross-country to the butte’s base. |

|

|

|

|

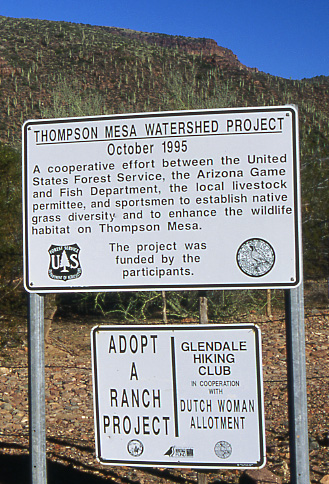

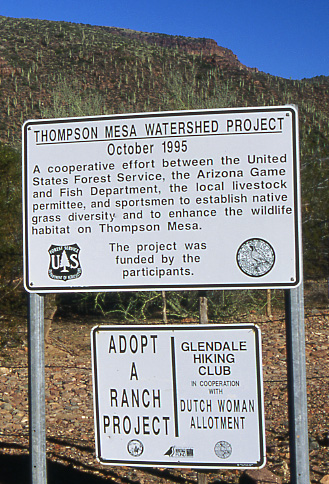

A short walk on FR 895 north of my camp brought me to this cattle fence and amusing sign. Hikers unaware of how a healthy grassland should look (as on the butte’s summit) might be misled regarding the environmental conditions on the surrounding cattle allotment. Let’s take a look at it. |

|

| This region annually averages 17" of precipitation, not enough to sustain large herds of large ungulates—neither cattle nor wildlife. Without water developments like this windmill and storage tank, ranching here would be impossible. But just because cattle can then survive here doesn’t mean that the ecosystem will remain healthy. On the contrary, the consequences of cattle grazing for the environment are devastating as cattle devour practically every plant except the shrubs and cacti. |

|

With much of the vegetation removed by cattle, topsoil becomes more vulnerable to erosion. Eventually only gravel remains. Cattle also damage the deeper soil by compacting it with their hooves and by depositing concentrated nitrogen from their dung and urine. All these factors would slow the return of native grasses even if cattle were permanently removed from the region. |

|

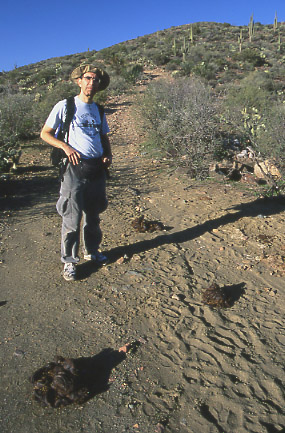

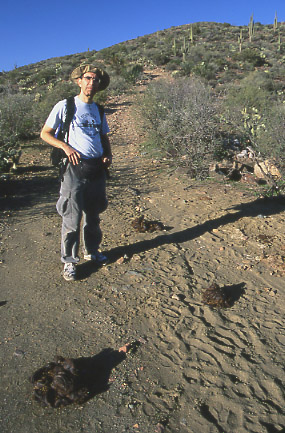

Farther up the road, evidence of yet another impact of cattle: inefficient nutrient cycling. Ecosystems with large native ungulates typically also have dung beetles that facilitate the decomposition of dung. Since no large ungulates are native to this region, there are no dung beetles. Consequently, cow dung can remain intact for months or even years. |

|

Upon coming even with the northeast corner of Dutchwoman Butte on FR 895 it’s time to set off cross country. From here to the summit it’s a one mile trek with a 700-foot elevation gain over rocky ledges covered with cacti and thorny shrubs. Even this least difficult of routes has proved an impenetrable barrier to cattle. |

|

| On the summit one enters a world markedly different from that of the surrounding terrain. Here, in the absence of cattle, we marvel at the diversity, density, and vigor of a dozen grass species. Most of the

grama grasses reach knee height with some species such as

cane beardgrass and

green sprangletop growing even higher. All that biomass will eventually decompose to contribute excellent topsoil to that already here, the organic carbon content of which has been measured at three times the norm in Arizona. |

|

|

|

| Compare the image of the ungrazed summit on the left with the grazed lowlands on the right. These semi-desert grasslands might again resemble the butte’s summit, but not before a long period of natural restoration beginning with the permanent removal of cattle. |

|

|